Earthy

Tonesof Georgia O’Keeffe

New Mexico, a source of inspiration with an earthy color palette that embodies “lightness”, the theme of this season’s collection.

Here’s a look at the life and times of artist Georgia O’Keeffe, a long-time resident who loved these rocky desert spaces.

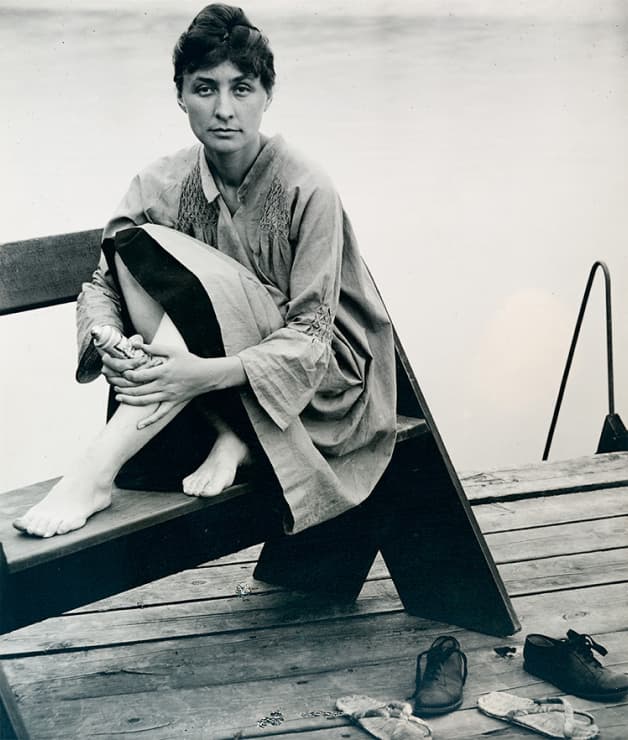

Photo by Tony Vaccaro / Abiquiú, New Mexico, 1960 / Archive Photos / Getty Images

Georgia O’Keeffe

Painter, Artist

Born in 1887, Georgia O'Keeffe has been called the mother of American modernism. Debuting in 1917 with a solo show in New York, she created iconic works that won critical acclaim, like her close-ups of flowers. After losing her husband in 1946, she relocated to New Mexico, where she lived and worked until her death at ninety-eight.

I’ll paint what I see.

Georgia O’Keeffe. As the preeminent woman working in the US art world in the twentieth century, she holds a place held by no other to this day. With her works depicting flowers, skyscrapers, and animal skulls resting on dry earth, her dramatic life story, and her countenance of solitary independence—she has long been viewed as an icon, though she lived her life on her own terms, free from the labels that such expectations foist upon an artist.

Born in 1887 in Wisconsin to a farming family, O’Keeffe enjoyed drawing from an early age. After studying at the Art Students League in New York, she worked as an art teacher in Texas high schools and later taught in South Carolina, devoting time to art all the while. This was an era when the modern art of European artists like Matisse, Picasso and Braque was first arriving in the US. The young O’Keeffe was deeply moved by these avant-garde expressions.

The story of how she reached the highest echelons of art is nothing short of legendary. In 1915, O’Keeffe sent some abstract charcoal sketches to a friend in New York, who showed them to the world-famous photographer Alfred Stieglitz. An influential figure in the art world, Stieglitz was so stunned he shouted, “At last, a woman on paper!” Without O’Keeffe’s permission, he exhibited these works at his gallery “291”, in what turned out to be her debut as an artist. Thereafter, O’Keeffe developed a relationship with Stieglitz, who was married and twenty-three years her senior. Over the course of numerous letters, a romance blossomed. The two were wed in 1924, when O’Keeffe was thirty-seven.

Vigorously promoted by Stieglitz, she soon gained a reputation as a major figure of modernism. Among the works created in this period are her classic oil paintings of flowers. These radiant paintings depict flower petals at a scale rarely encountered in still lifes. Abstract in their own way, they were not only beautiful but brimming with a rich vivacity.

Ghost Ranch Home, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

O’Keeffe’s home in the Ghost Ranch area of New Mexico, purchased in 1940. Built in a traditional style, this adobe ranch has an area of 184 m².

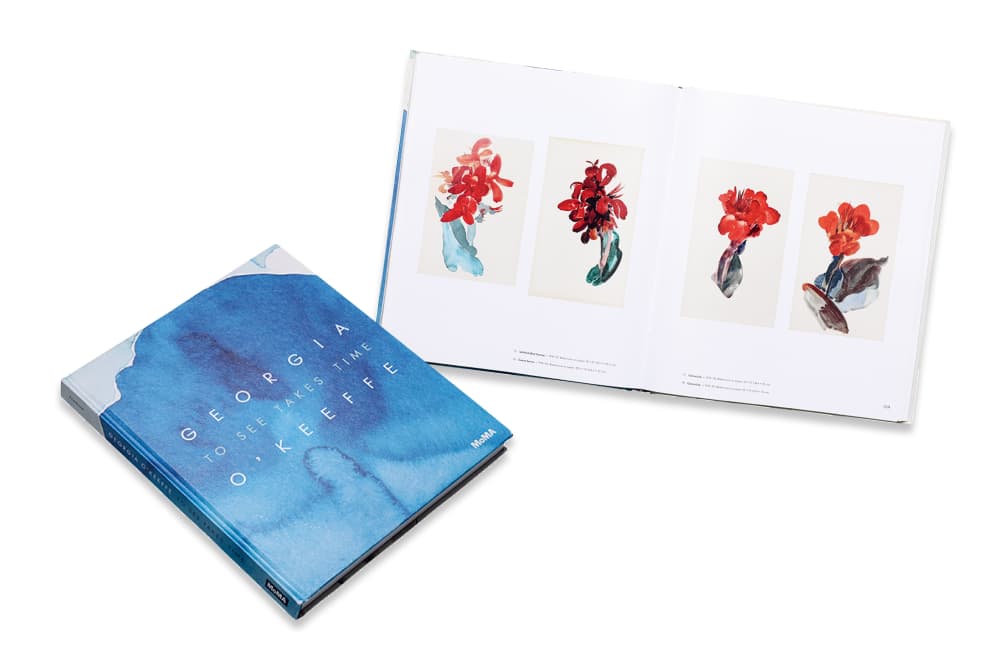

Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time

Edited by Samantha Friedman, 2023 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Catalog published by MoMA for 2023 O’Keeffe show. Around 200 of the 2,000 works she left behind depict flowers, with a special focus in the late 1910s and 1920s on red canna lilies like those shown here.

Georgia O'Keeffe. No.12 Special, 1916. Charcoal on paper, 24 x 18 7/8 inches. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation [1995] (200.95)

Early charcoal drawing by O’Keeffe. Shown at photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery “291”.

Alfred Stieglitz. Georgia O'Keeffe, 1918-1919. Gelatin silver print, 8 11/16 x 7 7/16 inches. Museum Purchase. [2014.3.56]

1918 portrait of O’Keeffe at thirty-one, taken by photo-grapher Alfred Stieglitz, who she would later marry.

Georgia O'Keeffe. Flower Abstraction, 1924. Oil on canvas, 48 x 30 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; 50th Anniversary Gift of Sandra Payson [1985] (85.47)

Among O’Keeffe’s zoomed-in floral abstractions, this early work from 1924 stands out. The many layered gradations are exquisite.

“Nobody sees a flower – really it is so small – we haven’t time...So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.” (from “About Myself,” 1939 catalog) .

Acclaimed and renowned, O’Keeffe was finding herself increasingly distressed. Above all, she was fed up with reductive understandings of her work as feminine or sensual. At a time when the art world was dominated by male voices, from the universities and museums to the critics, O’Keeffe was something of an outlier. As her fame grew, she longed for a place where she could make her work in peace, but Stieglitz was a socialite, always inviting people over and not shy about his interest in other women. In 1929, worn down by this lifestyle, she and a female friend boarded a steam train bound for New Mexico in the Southwest.

Badlands sparse in vegetation, mounds of ragged rock. O’Keeffe was taken by the palette and texture of the high desert, so different from the tree-covered East Coast. In 1934, she moved to Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiú, where she found a little house made from adobe. It was a remote outpost with no telephone or water, the nearest place to buy food over 40 km away. Standing in her yard, she had a clear view of Cerro Pedernal, a mesa (table-shaped plateau) characteristic of the region. Once underwater millions of years ago, these foothills comprise countless layers of sediment, creating a complex coloration. “All the earth colors of the painter’s palette are out there in the many miles of bad lands. The light Naples yellow through the ochres – orange and red and purple earth – even the soft earth greens,” O’Keeffe writes in a voice of irrepressible emotion, calling this land “our most beautiful country.”*

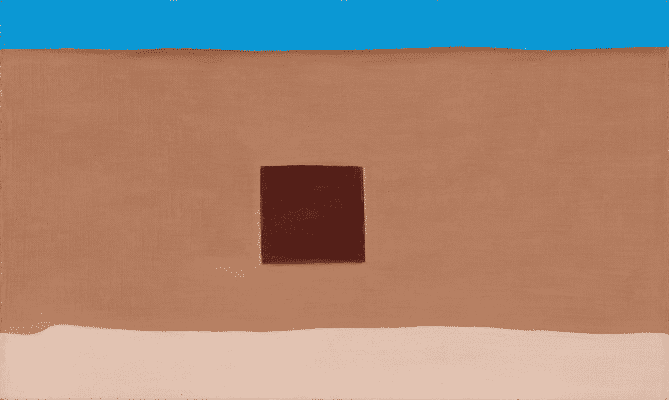

Georgia O'Keeffe. In the Patio VIII, 1950. Oil on canvas, 26 x 20 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. [1997.5.8]

Photo: Tim Nighswander/IMAGING4ART

Abiquiú Courtyard, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

1. Abstract painting calling to mind the garden door of Abiquiú house. 2. Animal horns on display at home. An important motif. 3. Rock collection on a windowsill.

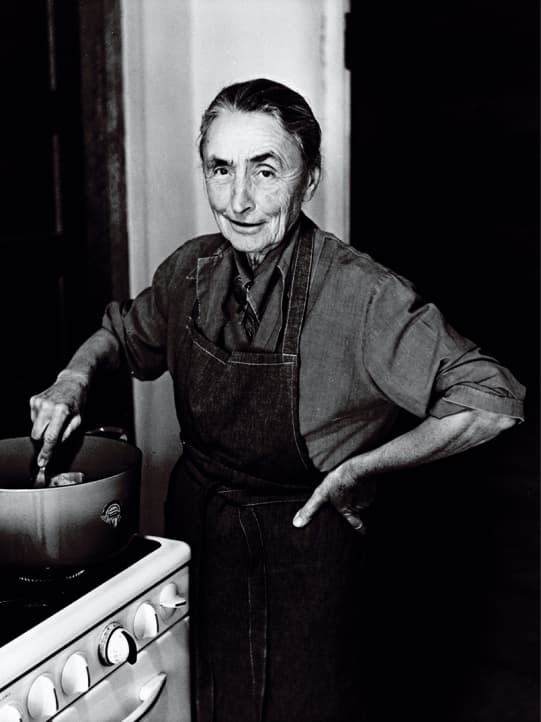

Todd Webb. Georgia Making Stew, Ghost Ranch, 1962. Gelatin silver print, 6 3/8 x 5 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Todd Webb Archive. [2006.6.985]

Ghost Ranch Breakfast Nook, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

4. O’Keeffe liked to cook. 5. The “breakfast nook” in Ghost Ranch, two walls of which are big glass windows. Sitting on the bench, O’Keeffe could view the majestic landscape over her morning meal. She had a fondness for teapots from China and Japan.

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Ghost Ranch Studio, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

Abiquiú Closet, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

6. Paintbrushes from the studio. 7. Red lounge chair from Herman Miller designed by Charles and Ray Eames, her personal acquaintances. 8. Closet at the Abiquiú house. Black clothes, like this robe, abound.

Georgia O'Keeffe. Lavender Hill with Green, 1952. Oil on canvas, 12 x 27 3/16 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. [1997.5.10] Photo: Tim Nighswander/IMAGING4ART

© Sophie Isogai

Colorful sandstone hills evoke the landscape of New Mexico. O’Keeffe painted them repeatedly, with changing times and seasons.

Few visitors made the trek out to Ghost Ranch. Once she had felt the quiet of the desert soothe her heart, she traveled there each year to paint. Bleached bones sitting underneath wide-open skies, skirted by hills. When Stieglitz passed away in 1946, she moved there permanently. O’Keeffe renovated a house with a garden in the neighboring village of Abiquiú and began using this as her home in the winter and spring, heading to Ghost Ranch for the summer and fall. Assistants took care of her everyday concerns, allowing her to focus on her painting. In her spare time, she liked to cook, listen to music, or tend the garden. The well-lit living quarters may have been modest, but she selected her appliances with care.

During her time in New Mexico, O’Keeffe developed a strong interest in the culture of the Pueblo peoples who had lived in this land since ancient times. With silt and clay, they built homes and made tools, hunting as they farmed grains and maize. In constant communion with the natural world, they led lives rich with spiritual traditions. In the words of Cody Hartley, director of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum,

“One of the reasons O’Keeffe was so fascinated by indigenous cultures is that she was trying to find something authentic or universal, searching for alternatives to capitalism and progressivism. Authentic expressions of human experience, genuine and sincere. O’Keeffe’s work is not concerned with time or storytelling. It isn’t sentimental. It simply exists in this world as an object of contemplative beauty. In the art world at the time, there was no one like her.”

By the 1970s, O’Keeffe had suffered from macular degeneration, which gradually worsened until she was left with only peripheral vision. It’s hard to imagine what it’s like for an artist to lose their sight. But thanks to the help of her staff, O’Keeffe continued to express herself through drawing and even took up clay, seeing with her hands. She lived on this land that had unblocked her heart until she passed away at ninety-eight. When this artist, so true to her emotions, looked at a flower “nobody saw,” what did she see? Perhaps the answer can be found in the landscape of New Mexico, which she observed like nobody before or since.

*Henry McBride. “Sees Mountains Red.” Reprinted in Georgia O'Keeffe and Her Houses by Barbara Buhler Lynes and Agapita Lopez. Harry N. Abrams, 2012.

Georgia O'Keeffe. Above the Clouds I, 1962-1963. Oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 48 1/4 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. [1997.5.14] Photo: Tim Nighswander/IMAGING4ART

1960s cloud painting made by O’Keeffe in her seventies. Said to be inspired by the view seen from airplanes on her travels around the world.

Todd Webb. Georgia O'Keeffe and Chows in Abiquiu Garden, ca. 1962. Chromogenic print, 5 x 3 1/2 inches. Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation. © Todd Webb Archive. [2006.6.1035]

Though O’Keeffe lost her eyesight as she aged, she picked up ceramics with the assistance and encouragement of potter Juan Hamilton. Many of these works are held at the Abiquiú house.

Ghost Ranch Bedroom, 2019. Krysta Jabczenski. © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum.

- 1887

- Born on a farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin.

- 1916

- Studies with Arthur Dow at Columbia University Teachers College, learning principles of Japanese art.

- 1917

- First solo show at “291”, photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s New York gallery.

- 1924

- Three months after Stieglitz finalizes his divorce, they marry.

- 1946

- Stieglitz dies of a fatal stroke. The next year, O’Keeffe relocates permanently to New Mexico.

- 1970

- Retrospective opens at Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

- 1986

- Dies at ninety-eight in Santa Fe. The next year, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC hosts a major retrospective.

© 2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

- Text by Kosuke Ide

- Coordination by Chinami Inaishi

- ไทย

- English

Release dates vary depending on the product.

All listed prices, current as of February 12th, include sales tax and are subject to change.