Build

the Future

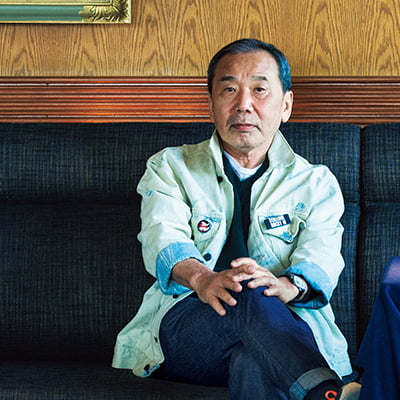

Interview with Tadao Ando

- Photograph by Keisuke Fukamizu

- Text by Kosuke Ide

The creator of a succession of buildings that challenge the truisms and fixed ideas of architecture, world-renowned architect Tadao Ando has been engaged in a variety of social activism throughout his career.

At the Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest in Osaka, a library for children that was spearheaded by Ando himself, this fighting architect indulged us with some words of wisdom.

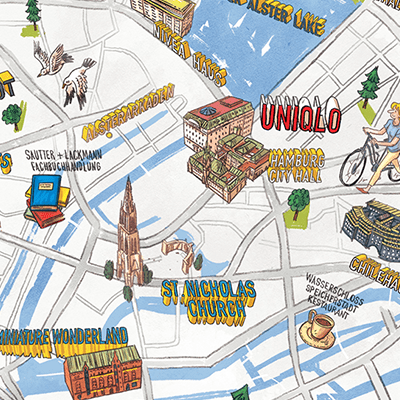

Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest

The three-story 800 m² space, which Ando designed himself, contains 18,000 purchased or donated books.

1-1-28 Nakanoshima Kita-ku, Osaka-shi,

Osaka-fu 530-0005 Japan

- Tadao Ando

- Architect

Born in 1941 in Osaka. Founded Tadao Ando Architect & Associates in 1969. Became a professor at the University of Tokyo in 1997 and professor emeritus in 2003. His many works include Japan Pavilion for Expo ‘92, Church of the Light, Osaka Prefectural Chikatsu Asuka Museum, Awaji Yumebutai, Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Punta della Dogana, and Bourse de Commerce. He was awarded the Annual Prize of the Architectural Institute of Japan in 1979 for Row House in Sumiyoshi, and the AIA Gold Medal by the American Institute of Architects in 2002. In 2010, he was conferred the Order of Culture.

“Alright everybody, let’s take a picture!”

When Tadao Ando walked in the building and strode gallantly downstairs into the lower level, making this announcement, children all over the building left their books where they were sitting and gathered around. Stunned at this surprise visit from the designer of the Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest, which opened just last summer in Osaka, their guardians welcomed Ando with a flurry of photographs.

“You can make the best library in the world, but you can’t make every kid who visits fall in love with reading. If we get through to one out of ten kids here today, we’ve done our part. Who knows, maybe they’ll look back on how they took a picture with Tadao Ando at that interesting library. Experiences like this can be enough to make a reader out of you.

As sunlight pours into the atrium-like space through a bank of windows, children roam about picking whichever books they like, exploring the three floors of shelves as if they’re walking through a forest. Ando had a vision to create the ideal library for kids on Nakanoshima, an island in the middle of Osaka that has long played a role in government, economics and culture in the city. This cultural institution was proposed and designed by Ando himself and constructed at his own expense.

“The city government gave us the greenlight to build on public land, but without supplying any funds for construction or operation. So I provided the building expenses, and we solicited contributions to cover operating costs. If you can get 200 people who’ll contribute 300,000 yen, that’s 60 million yen right there. Enough to keep things going for a year. But when we went around to mostly local businesses, asking for folks to pledge 300,000 yen a year for five years, we amassed over 600 contributions, surpassing our objective. In five years, we’re expecting to have raised about 1 billion yen.”

Ando deftly illustrates his explanation using numbers, as if clicking through an abacus, but it was undoubtedly no small thing to amass this much money in donations, let alone personally fund such a big-ticket project. What allowed him to clear the countless hurdles and make the building a reality was his enthusiastic support for the future of children.

“Kids today will create the society of tomorrow. To cultivate their minds and help these kids learn to think for themselves, we need to provide them with books. But for a while now, the economic focus of Japanese society has encouraged an educational approach where kids are taught to ‘avoid irrelevant reading and focus on practical skills.’ The adult world is only ever chasing sales and profits. I was born into a typical working class neighborhood in Osaka, and my home environment was not exactly cultured. Growing up, there were no books around. Looking back, I wish I could have read all kinds of books when I was young and impressionable, all my senses sharp. Still, we had so much freedom back then. Today’s society is obsessed with efficiency, while education revolves around test results, leaving few people who think for themselves. Nothing is more important to our lives than freedom. And if we want to keep that freedom, we’re going to have to fight.”

Indeed, Ando is often viewed as a “fighting architect.” An early passion for boxing led to a brief stint in the pros while he was still at technical high school. Later, he studied architecture independently when he wasn’t working part-time jobs, never receiving any formal education at a university.

“I worked like crazy, convinced I had to study harder than someone who’d gone to school. By cutting back on food expenses, I managed to buy the textbooks college students read in the top-level programs and spent my lunch breaks at my job studying architecture.”

In his early twenties, he traveled widely in Japan and abroad, paying witness to iconic examples of Japanese and Western architecture. In 1969, at twenty-eight, he opened his own studio. Since the 1970s, he has created a succession of radical buildings, from homes to public facilities, that positively challenge the truisms and fixed ideas of architecture, establishing himself as an international figure.

Meanwhile, Ando is also known for having engaged in a wide variety of social activism that falls outside the framework of architecture. One such project is the Setouchi Olive Foundation *1, whose mission is to plant one million olive trees on the coasts and islands of Japan’s Inland Sea.

*1 Setouchi Olive Foundation:

Established in 2000, in response to the Teshima incident, to protect and resuscitate the landscape of the Inland Sea. Of the 285,000 m2 that were ravaged, greenspace has been restored to 3,980 m2 of land. Over 1,500 people have volunteered to gather marine debris and plant trees. Endorsing these efforts, UNIQLO stores have been collecting funds since 2001, with GU stores participating since 2011. By the end of 2019, some 600 million yen had been provided to a total of 369 organizations tackling environmental issues.

Situated on the edge of the Dojima River, the library has a gently curved facade, and the interior capitalizes on the convex lines of the design. The second floor has a floating walkway, from which most of the faces in the library can be viewed at once.

“Now that we can access information easily over the internet, almost to the point where we can’t turn it away, it’s so important for kids to make conscious choices and use their own two hands to pick out books to read,” says Ando.

Indeed, Ando is often viewed as a “fighting architect.” An early passion for boxing led to a brief stint in the pros while he was still at technical high school. Later, he studied architecture independently when he wasn’t working part-time jobs, never receiving any formal education at a university.

“I worked like crazy, convinced I had to study harder than someone who’d gone to school. By cutting back on food expenses, I managed to buy the textbooks college students read in the top-level programs and spent my lunch breaks at my job studying architecture.”

In his early twenties, he traveled widely in Japan and abroad, paying witness to iconic examples of Japanese and Western architecture. In 1969, at twenty-eight, he opened his own studio. Since the 1970s, he has created a succession of radical buildings, from homes to public facilities, that positively challenge the truisms and fixed ideas of architecture, establishing himself as an international figure.

Meanwhile, Ando is also known for having engaged in a wide variety of social activism that falls outside the framework of architecture. One such project is the Setouchi Olive Foundation *1, whose mission is to plant one million olive trees on the coasts and islands of Japan’s Inland Sea.

※1 Setouchi Olive Foundation:

Established in 2000, in response to the Teshima incident, to protect and resuscitate the landscape of the Inland Sea. Of the 285,000 m2 that were ravaged, greenspace has been restored to 3,980 m2 of land. Over 1,500 people have volunteered to gather marine debris and plant trees. Endorsing these efforts, UNIQLO stores have been collecting funds since 2001, with GU stores participating since 2011. By the end of 2019, some 600 million yen had been provided to a total of 369 organizations tackling environmental issues.

1. Teshima in Kagawa Prefecture, floating in the Inland Sea. For over ten years, toxic waste was illegally dumped on the west side of the island (bottom of photo).

photographs by Hiroshi Fujii

2. Site of dumping. For sixteen years, until 2019, around 910,000 tons of waste were recovered and processed.

photographs by Hiroshi Fujii

3. View from an olive orchard.

photographs by Kei Kobayashi

“I was invited by Soichiro Fukutake of the Benesse Corporation to participate in his grand scheme to make the island of Naoshima a hotspot of modern art, and I’ve taken part in the design of a series of buildings since the late 1980s. In the process, I learned about the toxic waste problem that the island of Teshima in Kagawa Prefecture had been facing. Teshima used to be a verdant place, but in the 1970s it was subject to illegal dumping of industrial waste, devastating the local ecosystem and causing pushback from the island’s residents. Viewing the incident as emblematic of environmental devastation in Japan, I teamed up with the lawyer Kohei Nakabo, who had fought for Teshima in the trials, and psychologist Hayao Kawai (both of whom have since departed) to establish a tree-planting initiative, in the hopes of reinvigorating the natural landscape of the area. No sooner had we started up in 2000 than Tadashi Yanai, head of Fast Retailing, offered his support, leading us to collect funds at stores and establish a steering committee. Over the past twenty years, we’ve planted 170,000 trees and begun supporting a variety of environmental NPOs, a fairly modest achievement. Abatement of the toxic waste was finished in 2019, but the problem remains of treating the polluted water. We still have a long way to go before we can say we’re finished.”

Ando is also responsible for the Umino-Mori project, where 500,000 saplings were planted at a landfill in Tokyo Harbor, and Sakura No Kai, an organization that planted 3,000 cherry trees on Nakanoshima in Osaka with the help of local volunteers, beautifying the city through a new form of community-building. He has devoted his time and energy to a number of other environmental causes as well.

“For ages, the people of Japan, an island nation, lived in a lush natural landscape, surrounded by the ocean on all sides. There was a time when the culture revolved around families and communities working hand in hand. Unfortunately, the beauty of the Japanese landscape has been gradually depleted. I think this has to do with how Japan became an economic superpower in the 1970s, and despite the bubble bursting in the 1990s, society continues to interest itself primarily with economic development. I see this problem as behind all kinds of other issues, like global warming and the coronavirus. After generations living among nature, we’ve lost touch with the natural world. Clearly this has resulted in a slew of problems for contemporary society. We have a responsibility to the next generation of children who will live in the world to come. Something must be done.”

Living among nature, and living hand in hand. Ando’s efforts to ensure a better future go beyond a purely environmentalist approach. After the Great Hanshin Earthquake hit Japan in 1995, he established the Hyogo Green Network, which planted trees in memoriam for the departed, as well as the Momo-Kaki Orphans Fund *2, created to support children who lost parents in the disaster. His efforts raised 500 million yen in ten years, supporting 418 children who have lost their parents. Following the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, he launched a similar relief fund. In the past ten years, they have raised 5.2 billion yen for the three prefectures hit the hardest, more than any other organization, allowing them to help 1889 unparented children.

*2 Momo-Kaki Orphans Fund:

Founded by eight philanthropists, including Ando, in the hopes of helping children who lost guardians in the Great Hanshin Earthquake to lead wholesome lives. In May 2011, Tadashi Yanai joined their Great East Japan Earthquake Orphan Education Fund as a founding member. The name “Momo-Kaki” comes from an aphorism about peach and chestnut trees taking three years to reach fruition, while persimmon trees take eight, a metaphor for the fund’s longterm commitment to assisting children.

4. Children planting olive trees.

5. Stone marker engraved with Ando’s words: “Toward a Greener Inland Sea.”

“I’m not trying to make some special contribution to society. I’m simply attempting to preserve the world around us. We cannot act like nature isn’t there. It needs regular maintenance. Like how relationships demand frequent attention. That’s why I get involved. Reaching out to people who need help. It’s the only way we’re going to survive. But you can only help others if you have strength to spare. Strong in body and in mind.”

Pictured by the entrance to the Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest, in front of the green apple which Ando describes as “symbolic of youth.”

Fighting to preserve the world around us. At eighty years old, where does Ando get his limitless supply of energy? Incredibly, since being diagnosed with cancer in 2009, he has had surgery to remove his duodenum, bile duct, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen.

“That’s life. This sort of thing happens. When I asked the surgeon if I could live without all five of those organs, he said, ‘You’ll live, but it won’t make you stronger.’ Since surgery, I’ve been taking daily walks, and spend about forty minutes on each meal. When I’m done eating, I have to take a break. But I’m able to make good use of the time, thinking or reading. They say that no one else has ever been this healthy after surgery.”

Ando spoke enthusiastically for almost two hours that day, with a vitality that could rightly be called superhuman.

When I asked him where his power comes from, he answered, without hesitation, “I have work to do. Things I want to see through to completion. Plans are in the works to build children’s libraries in Kobe and Tono, in Iwate Prefecture. I’m personally funding these projects as well. But as much as I’m ready to go, it can be hard to find a place to host these projects. Operation costs are a sticking point. Sometimes people see me doing this stuff and say, ‘Ando, with all the work that you have on your plate, why bother using your own money to build something?’ The way I see it, it’s fine for one person in a thousand to act like this. Maybe if one person does this kind of thing, others will follow. I figure, you only live once, so I may as well use up the money I have. The point isn’t to make the most beautifully designed building possible. No building lasts forever. But the impressions they create can last forever in the soul. After all, being alive is all about self-expression. My goal is to create buildings that will last forever in the hearts of people who experience them. But life doesn’t really go as planned, now does it. The second you tell yourself that things are going well, they fall apart. Over and over. You need to brace yourself and stick it out.”

In Ando’s words, “Japanese people today don’t have any money or enthusiasm. All they have is pride. They can’t see the future.” After describing an assortment of dilemmas, no way to turn, this architect who has made a career out of fighting and defying the odds smiled.

“We need to find a way to get back on our feet. Before we built Awaji Yumebutai, it was an abandoned quarry, and thirty years before we started planning, there were no trees in sight. The situation changed once people stepped in and planted saplings, and now it’s home to a huge forest. Things work out if you try. If you give it your all, as if your life depends on it, you can make anything happen.”

Pictured by the entrance to the Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest, in front of the green apple which Ando describes as “symbolic of youth.”

UNIQLO TOP

UNIQLO TOP